- EU projects

- Research

- Fish tagging

- Lumpfish research

- Oceanography

- Seabed mapping

- Arnarfjörður

- Drekasvæði

- Ísafjarðardjúp

- Jökulbanki

- Jökuldjúp

- Kolbeinseyjarhryggur and adjacent area

- Kolluáll

- Langanesgrunn

- Látragrunn

- Nesdjúp

- Reykjaneshryggur and adjacent area

- Selvogsbanki

- South of Selvogsbanki

- South of Skeiðarárdjúp

- South of Skerjadjúp

- Southeast of Lónsdjúp

- Southwest of Jökuldjúp

- Suðausturmið

- Suðurdjúp

- Vesturdjúp

- East of Reykjaneshryggur

- Vestfjardarmid

- Seal research

- Whale Research

- Advice

- About

Temperature effect on Polar cod distribution around Iceland

19. December 2025

Polar cod, a cold-water Arctic species inhabits the waters around Iceland which is the southern limit of this species. The photo is from the Swedish website www.fishbase.se.

Polar cod, a cold-water Arctic species inhabits the waters around Iceland which is the southern limit of this species. The photo is from the Swedish website www.fishbase.se.

Dr. James Kennedy and Dr. Christophe S. Pampoulie scientists at MFRI recently published a peer review research paper on the relationship between polar cod distribution and sea temperature around Iceland.

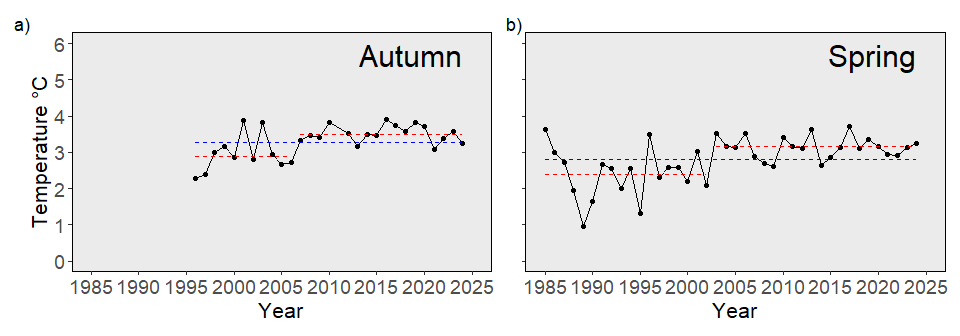

The seas around Iceland are influenced by the warm Atlantic water in the south and cold Arctic water in the North, with changes in these currents altering the environmental conditions in the waters around the Island. These changes can make the area more or less suitable for the fish that live there. Polar cod, a cold-water Arctic species and important prey for fish, birds and marine mammals, inhabits the waters around Iceland which is the southern limit of this species. Previous work from a decade ago documented a decline in the occurrence of polar cod with rising temperatures. A new study, which builds on this previous work by incorporating data from autumn as well as spring, looked at the distribution of Polar cod around Iceland, at what depths and temperatures it was most commonly found and how its distribution has changed with fluctuations in temperature (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Average bottom temperature over time of trawl stations north and east of Iceland during the spring and autumn trawl survey.

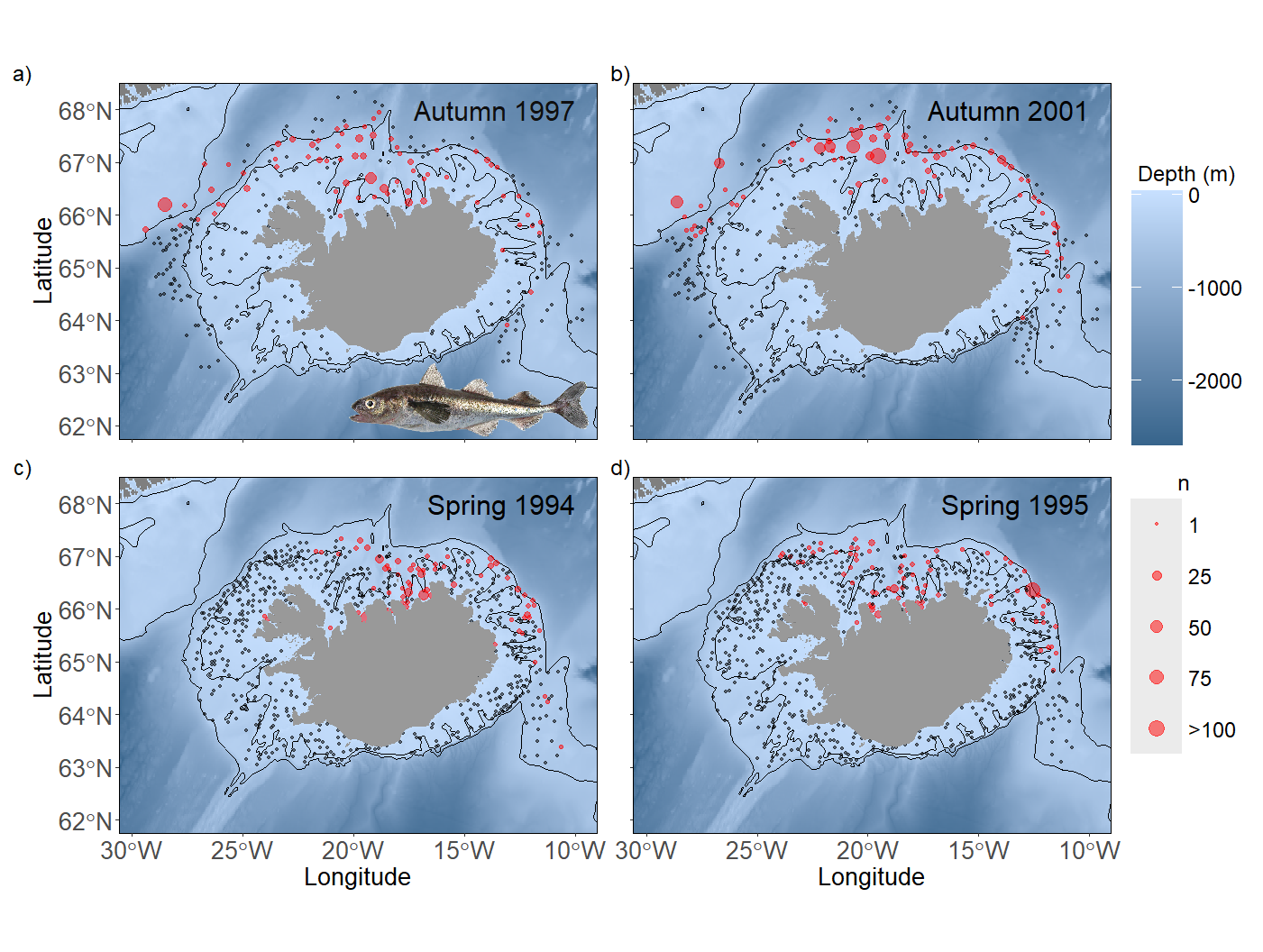

Dashed lines show average temperature of the whole time series (blue) and for limited time periods (red).

Polar cod are only caught in very small numbers during the spring and autumn groundfish survey, usually 1-5 individuals per trawl station, but these catches provide valuable information into the biology of the species. Catches of polar cod reveal that it is primarily restricted to the northwest, north and east of Iceland at depths ranging from 50 to 1,249 m but is most commonly found at 350-500 m (Figure 2). It is found at a wide range of temperatures during the autumn (1.8–9.0°C), but in the spring, they were rarely found at temperatures >3.5°C. The fact that polar cod eggs fail to hatch at temperatures >3.5°C may explain why polar cod are found in colder water during the spring, when they are thought to spawn. In the northwest, polar cod were restricted to deeper water in comparison to the east, as the shallower water in the west was too warm.

Figure 2. Location and number of polar cod caught during years of high occurrence in the spring and autumn survey.

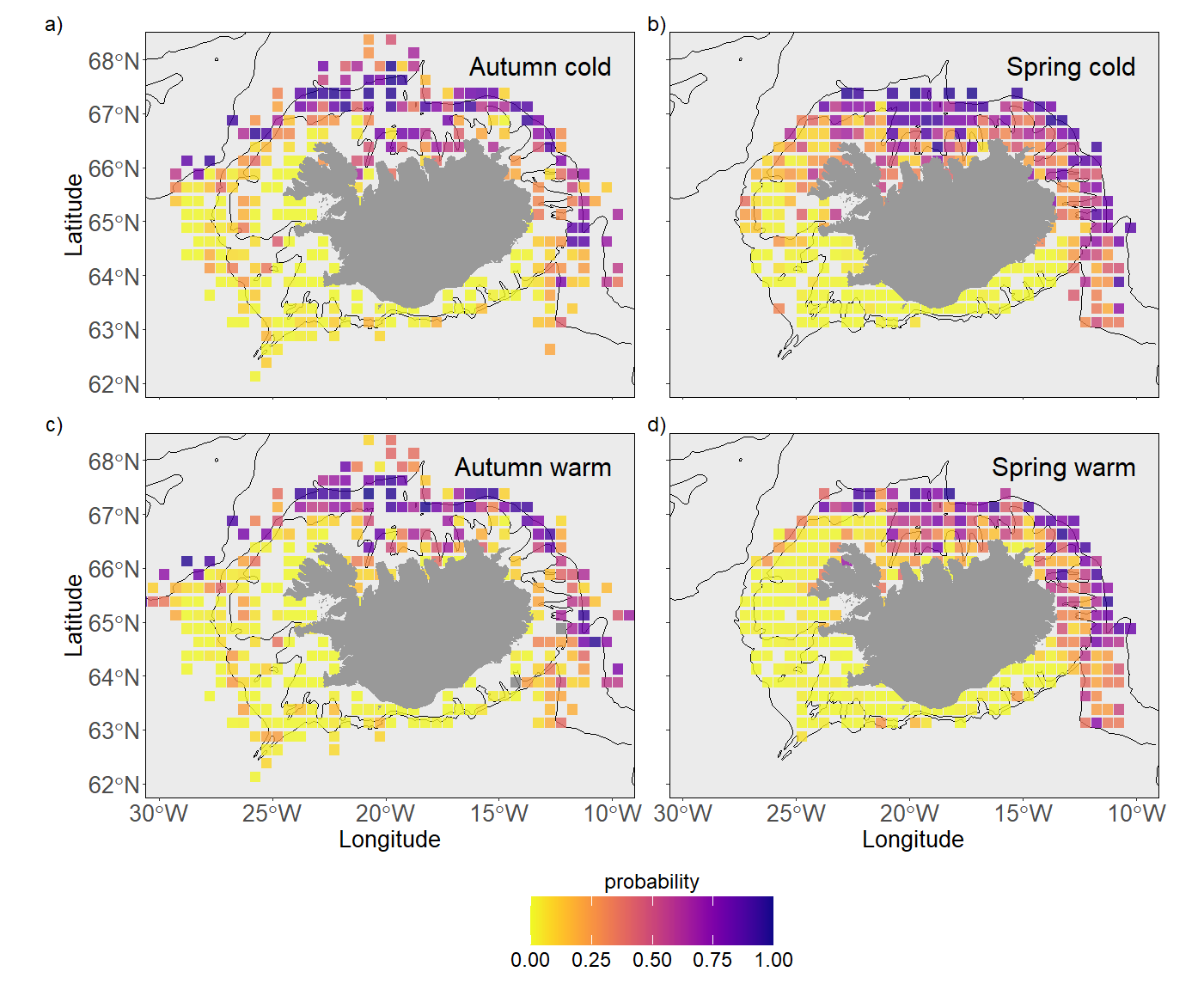

In years with warmer temperatures, polar cod would be present across a smaller area, retreating from shallower waters in the north and northwest to deeper colder waters (Figure 3). The change in distribution was much stronger in the spring than in autumn and may be linked to the need for colder temperatures for spawning. Knowledge on the population of polar cod in Iceland is still limited e.g. it is unclear if the eggs spawned in Iceland survive and if the population is self-sustaining or if it is dependent on the immigration of juveniles from other areas. However, it is clear that warming of the waters around Iceland decreases the habitable area for polar cod around the country, which could have consequences for any predators of this species.

Figure 3. Probability of capture of polar cod around Iceland during cold and warm years for the autumn and spring bottom trawl surveys.