- EU projects

- Research

- Fish tagging

- Lumpfish research

- Oceanography

- Seabed mapping

- Arnarfjörður

- Drekasvæði

- Ísafjarðardjúp

- Jökulbanki

- Jökuldjúp

- Kolbeinseyjarhryggur and adjacent area

- Kolluáll

- Langanesgrunn

- Látragrunn

- Nesdjúp

- Reykjaneshryggur and adjacent area

- Selvogsbanki

- South of Selvogsbanki

- South of Skeiðarárdjúp

- South of Skerjadjúp

- Southeast of Lónsdjúp

- Southwest of Jökuldjúp

- Suðausturmið

- Suðurdjúp

- Vesturdjúp

- East of Reykjaneshryggur

- Vestfjardarmid

- Seal research

- Whale Research

- Advice

- About

Hidden Complexity in Blue Whiting Stock Structure

13. November 2025

Blue Whiting. Photo: Svanhildur Egilsdóttir

Blue Whiting. Photo: Svanhildur Egilsdóttir

Two new studies led by the University of Iceland in collaboration with the Marine and Freshwater Research Institute uncover hidden stock structure in Northeast Atlantic blue whiting, a key species for ecosystems and fisheries. The findings highlight distinct subpopulations, migration–residency dynamics, and the need for adaptive management in a changing ocean.

Blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassou) is one of the most abundant fish species in the Northeast Atlantic. As a benthopelagic species undertaking large-scale seasonal migrations, it forms a vital link in the marine food web — transferring energy from zooplankton to higher predators such as cod, mackerel, seabirds, and marine mammals. At the same time, blue whiting underpins one of the region’s largest commercial fisheries, making it a species of both ecological and economic importance.

Two new scientific studies, led by the University of Iceland in collaboration with the Marine and Freshwater Research Institute and international partners from Norway, Faroe Islands, Portugal, and Greenland, provide fresh insights into the population structure and distribution of blue whiting. The work was supported by the Icelandic Research Fund (Rannís) and the Nordic Marine Science network (NoRA). Together, the findings challenge the traditional view of the species as a single uniform stock and point towards more adaptive approaches for sustainable management.

More than a Single Stock

For decades, blue whiting across the Northeast Atlantic have been assessed as a single stock. But a new review published in Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries brings together genetic, chemical, life-history, and ecological evidence to show a different story. The species appears to form a metapopulation — a network of resident and migratory groups that mix in some regions but remain distinct in others (Figure 1).

This more nuanced picture highlights northern and southern migratory subpopulations, seasonal mixing zones, and local resident groups. Recognising this structure is essential, as treating blue whiting as one uniform stock may overlook biological realities that affect how populations respond to fishing pressure and environmental change.

Figure 1: Distribution of blue whiting in the Northeast Atlantic, showing distinct population structures identified in the research. Colours represent different subpopulations: northern (orange), southern (red), central (light-green), fringe (purple), resident (green), and mixing (blue) zones. Each group is labelled on the map according to its main geographical range. Main spawning areas are shown as solid black lines; seasonal migratory routes as dashed black lines. Note that the light-green shading (central population) overlaps parts of the northern and southern structures, including into Icelandic waters. This overlap may make it less distinct.

Icelandic Waters: A Key Piece of the Puzzle

In a companion study published in Marine Ecology Progress Series, the team focused on blue whiting in Icelandic waters, drawing on nearly three decades of fisheries survey data, collected during the spring and autumn. The results show that migration and residency both shape the population: large numbers arrive seasonally from the wider Northeast Atlantic, while smaller groups of juveniles remain year-round in nursery areas along Iceland’s southern and western shelves.

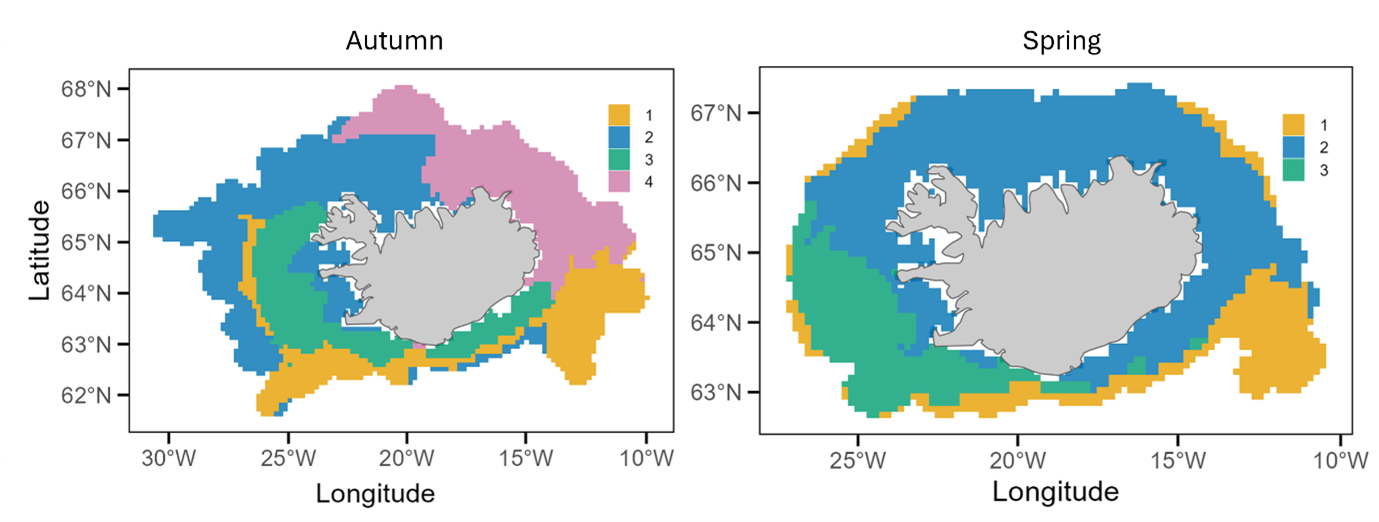

The analysis revealed four and three main local clusters of blue whiting around Iceland during the Autumn and Spring (Figure 2). Persistent aggregations were found along the southern shelf edge and the Iceland–Faroes Ridge (cluster 1), while deeper slopes to the northwest held fewer but larger individuals (cluster 2). On the southern and western shelves, variable numbers of smaller fish reflected changing recruitment over time (cluster 3), and the northeast shelf supported a smaller, distinct group with unique seasonal dynamics (cluster 4 – autumn only).

Environmental conditions such as depth (250-600 m), seafloor slope (0.5-1.5°), and water temperature (SST > 8°C) strongly influence where and when blue whiting occur, suggesting that climate change could alter their future distributions.

Towards Smarter Fisheries Management

Together, these studies highlight the need for adaptive, spatially-aware management that accounts for the species’ internal structure and changing environment. Moving beyond a “one-stock” view could improve the effectiveness of assessments, support sustainable harvests, and help safeguard the role of blue whiting in marine ecosystems.

By integrating new tools such as genomics, otolith chemistry, and advanced modelling, researchers aim to address key knowledge gaps about connectivity, life-history, and fine-scale structure. Together, these advances provide the scientific foundation for resilient fisheries management under climate change and reinforce the importance of international cooperation.

Figure 2: Hierarchical clustering results showing potential population structuring of blue whiting during autumn (left, late September to early November) and spring (right, late February to early April) from 1996 to 2023. Clustering is based on the median and coefficient of variation of occurrence, abundance, and weighted mean length. Temporal dynamics are represented by the loadings on the first principal component (PC1) of occurrence, abundance and length trajectories by (10 x 10 km) grid cell.